Corpso

"No man, you were Made in China."

In honor of the Halloween season, I thought I would share my famous “Corpso” story, a short essay about my dear and disgusting friend, Kyle.

I read this into a microphone once before a large group in a dark basement in Iowa City, Iowa. This was during grad school. All the other readings I had attempted and attended had been somber occasions with everyone, especially myself, trying to sound profound. And why not? Marily Robinson was teaching in the program that year, about to be interviewed by Barack Obama. Kurt Vonnegut, Philip Roth, and John Cheever had all taught there. Flannery O’Connor had begun as a student there. Raymond Carver had attended, Rita Dove, John Irving. Indeed, it takes an entire Wikipedia page to list the hundreds of writers who have graduated from Iowa and gone on to become famous or award-winning poets, fiction writers, and essayists.

Our work was supposed to be profound, important, serious and lasting.

“Corpso” was none of this, and in the three years I spent at Iowa I never received as many compliments or heard such a cascade of laughter as when I shocked the literati of the city with my profoundly low-brow ode to my best bro. Strangers demanded I forward them the story. They wanted to print it out, to mail it to their pals in Portland. It reminded them of their own washed up hipster friends. It was funny and it felt true; it was rude and real and ultimately reverent toward a highly decadent individual. There was something about the voice, they said, the persona of the narrator. It all felt so… true.

Everyone wanted to know, who was this Kyle character? Where had he come from? How had I cobbled him together? Was he… real?

I don’t know if this story is still any good. It’s been some years. At least it’s sort of Halloween themed. If I’m eventually going to leverage this blog into an international men’s lifestyle brand I need to keep posting, but it’s been tough between the nice new apartment, writing a horror screenplay about Father Junipero Serra, and fretting endlessly about the failure and futility of my book about the meltdown.

In any case, happy almost Halloween. Please Enjoy! And don’t forget to like and share…

Corpso

On road trips Kyle buys corn dogs so he can have diarrhea. He does this for fun. I showed him this trick, power through self-negation, and he stole it from me and perfected it. It was a quality he already possessed but I first noticed it and coaxed it out of him. It’s the tail side to monstrous confidence’s coin, a currency I lack.

Skateboarding in middle school, Kyle would try big tricks, long rails or huge gaps, daring his bones to break. Many times I saw him hurtling toward the ground and expected to hear a bare foot flatten a Dr. Pepper can, the sound of his spine piercing through the trachea, but like a cat he’d tuck and roll and stand up, dusting himself off and smiling.

Once after one of these falls, Kyle said that nothing could ever kill him. The rest of us stood dumbstruck, awed by his arrogance, an innate sense of karma offended, and nobody would try anything after that. Kyle always seemed to drink the last dregs of good luck, never saving anything for the rest of us, though sometimes he shared his sodas with me. They always tasted like cheese—he never cared to dig out the whitebread mash that collected in his front braces after his ham sandwiches. In high school, after he fed his dog his retainer, Kyle’s teeth turned crooked. He still rarely brushes them. The bottom row droops forward like some kind of rotten wooden fence, the pickets no longer white but dark-stained from years of tobacco smog. One tooth, however, the chipped left incisor, refuses to fall. He says it is a priceless adaptation that he needs to protect. He calls it his fruit tooth and he often scrapes peaches and apples to no avail on the sharp protruding piece of bone, letting the juice run down and dry uncomfortably on his neck.

In middle-school, to combat his pimples, he used to wipe pizza grease on his forehead and spray-paint his sandy hair pink. I don’t think it helped.

When people meet Kyle today they’re initially repulsed but gradually he burns through their first impression like a summer heat wave on a greasy play-palace window, working on them gently until eventually they see through the bacterial fog a beautiful brightness, a childlike man glowing with a jolly crooked smile, and they warm to him. I’ve seen cops with their hands held over their nightsticks yell at him to stop skateboarding, and then, five minutes later, they’re laughing, exchanging numbers with him, saying they’ll text him. Just last week, in a stranger’s kitchen, I watched Kyle squeeze through a ruck of females and fart boisterously, staring in each woman’s eyes proudly until they all burst out overjoyed and laughing.

Somehow, despite his best efforts, women find Kyle painfully attractive. They appreciate his life-affirming decadence. He has twice as many shirts as Gatsby but they all came from thrift stores. He doesn’t wash the ones that have stains from other people’s body odor but wears them proudly to work at an afterschool program where he supervises children’s arts and crafts. Part of Kyle’s success, I think, consists in the fact that he’s not much taller than his pupils: people may find him repulsive, but never physically threatening. His terrible thinning hairline adds a further layer of pathos. The kids make fun of him and he tells them not to touch it, that it took a long time to cut and glue all those individual threads of silk to his skull. Besides Kyle, I’ve never heard of anybody working a teaching job with a taxidermy possum tail dangling from the keys at the belt loop of their threadbare women’s jeans. Such things are possible though, I suppose, in Portland, where everyone is an artist or eccentric and shoddy local crafts like juvenile antler mounts, Earth-goddess oil paintings, and driftwood dildos pass for the commodity thrill everyone imagines they’ve transcended. But it’s not just a phase with Kyle. Kids pull out his hair and pigeons build nests with it. He does not imagine any infantile return to the earth. The irony he seems to wear in clothes and skin substitutes for the padding he refuses to wear in life. He has an anchor tattoo on his shoulder and one that says mom with a heart on his left forearm – clichés, irony. Kyle’s not particularly proud of his tattoos but he needs them. I think he would have burnt out long ago without this thin coating of ink to slightly dim his enthusiasm. People can call him what they like – hipster, faggot, fulsome sex-god – but whatever disparaging term they might fire, it never quite hits the mark. It’s hard to nail someone down when they’re always running past you.

An upside-down cross dangles from a chain at his right ear and collides with his skull while he skateboards home to dinner on windy days—the scabrous dramaturgy of a straight Jew who knows no wrecking ball. He is lucky, beautiful, a genius in this regard. He has succeeded in transforming himself into a most grotesque and wondrous cartoon character. It makes sense that he teaches kids and they love him. Outside a plasma television flatscreen, they’ve never seen anything quite like him. But is Kyle a good role model? Is his life sustainable? All those animated cartoon TV creatures, they always bounce back. No matter what happens, they reinflate and return the next episode. But Kyle? Only once did he need saving. An hour from sunset, wearing the wrong shoes while the fog rolled in, he decided to climb the cliff up the road from his house, the one on Cowles Mountain. Ten feet from the summit he got stuck. He saw the top had a slight overhang and he knew he’d never make it but he only started calling for help once the rocks got slick. A woman walking her dog, who turned out to be an ex-girlfriend’s mother, heard the faint cries. She had no idea it was Kyle. He was far away. We were at the end of high-school.

Local Man Rescued From Cliff, read the banner on the KUSI evening news. After the firefighters drove him home he called me over to watch. His mom made popcorn and while it cracked in the microwave she kept hitting him, calling him a stupid shit while he laughed. Then she sat down. His dad came in and crossed his arms. “Oh my God,” he said. The camera zoomed in and we saw a man marooned high above the road near the top of a cliff, a few hundred feet up the mountain. He stood on a narrow ledge facing the granite wall, feet pressed together with arms extended wide, holding onto the mountain like some reverse rock-crucified Christ. “A dramatic scene this evening here on Cowles Mountain as rescue crews attempt…” We watched the firefighters lower an emergency worker down the ledge on a winch. The newsman called Kyle’s climb questionable. “Why did you do that?” his mother asked. “So I could be on TV,” he said. Suspended at the middle of the flat screen, the stranded man looked scared. Kyle said that when he started calling for help, he almost fell. From the top of the cliff, his voice sounded so pathetic and small to him that he started laughing. “I would have been fine though,” he said, “There were some laurel trees down there. I could have jumped.”

A year ago, not long after Halloween, I gave Kyle the moniker Corpso. We were in San Diego then both visiting our parents for Thanksgiving. I met him in the black-painted bar in North Park, the one with all the Christmas lights and the tap handles hanging down like stalactites in a cave of glowing spiders, and for some reason then, sitting there drinking in the dim quiet, Kyle poured beer all over his face. People standing near the bar began to move uneasily away from our table. It was a stupid trick. I stared at him. With his execrable clothes, thinning hair, his acne scars and deformed incisors, I’d gradually begun to think of him not as a cartoon character but some kind of forsaken circus chimp, a once intelligent being that had slowly lost its mind performing the same dance routine every night over so many consecutive years. But in the smoky blue light of the bar that night, my vision changed. Kyle was thinner now and he looked older. The faded blood drive t-shirt was too big for him and hung baggy on his shoulders. It looked like a hospital gown. I saw clearly what he was then. I told him he looked like a dead body, like a corpse. The beer still shined wet on his face and the lashes were matted. “You’re ridiculous,” I said. I told him that over the years he had taken his routine, the power through negation gig, too far, to the point of truly undermining his dignity and destroying himself, so far that at times he didn’t really even seem like a person anymore, but a monster, a stubborn dead thing surviving on some frightening and undiscoverable integer of will: “You’re a fucking battery powered Halloween decoration,” I said. And when we left the bar I was calling him Corpso.

“You better stay out of the rain,” I said.

Kyle was happy – he’d gotten a rise out of me.

“What else is there?” he said. “It’s like Nietzsche, man, you have to learn to make your life into a work of art.”

I unlocked the car and he climbed in beside me.

“No, man,” I said. “I think you were made in China.”

Kyle clicked on the overhead light, lifted his leg and looked at the bottom of his shoe. “There’s no gold sticker,” he said

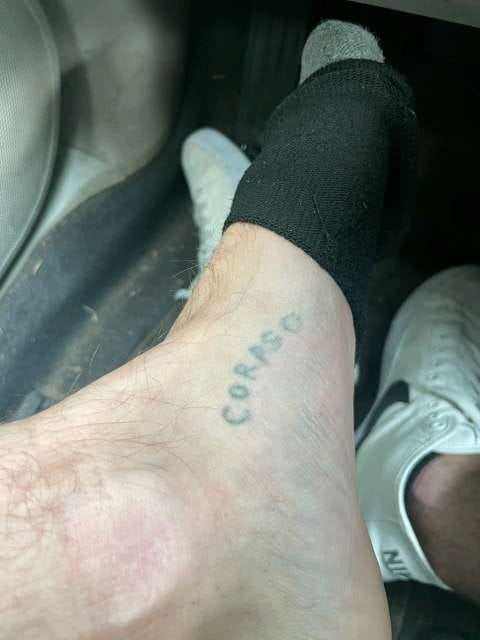

The next time I saw him he said he had a surprise for me. He took me in the bathroom, pulled down his pants and showed me his new tattoo. The word had been drawn in thin sloppy letters, as if he’d cajoled some child, one of his struggling pupils, into practicing cursive on his butt cheek – Corpso. “It looks good, right?” And this is what Kyle’s always done. He absorbs everything. One realizes they will never stall his growth, never offend or chop him down. Kyle assimilates every experience into his ongoing diversity and profusion, incorporates everything he can into his expanding vital core, and sometimes – just to be safe, so he’ll never forget – he carves it into a piece of skin. Kyle is only five-foot-four, but he’s truly monstrous. He never takes himself too seriously.

(Iowa City, IA, 2014)

In a different North Park bar, this one with red lights, you told me I looked like I had cancer. I did not get that tattooed on my body.

Love this. Love him.