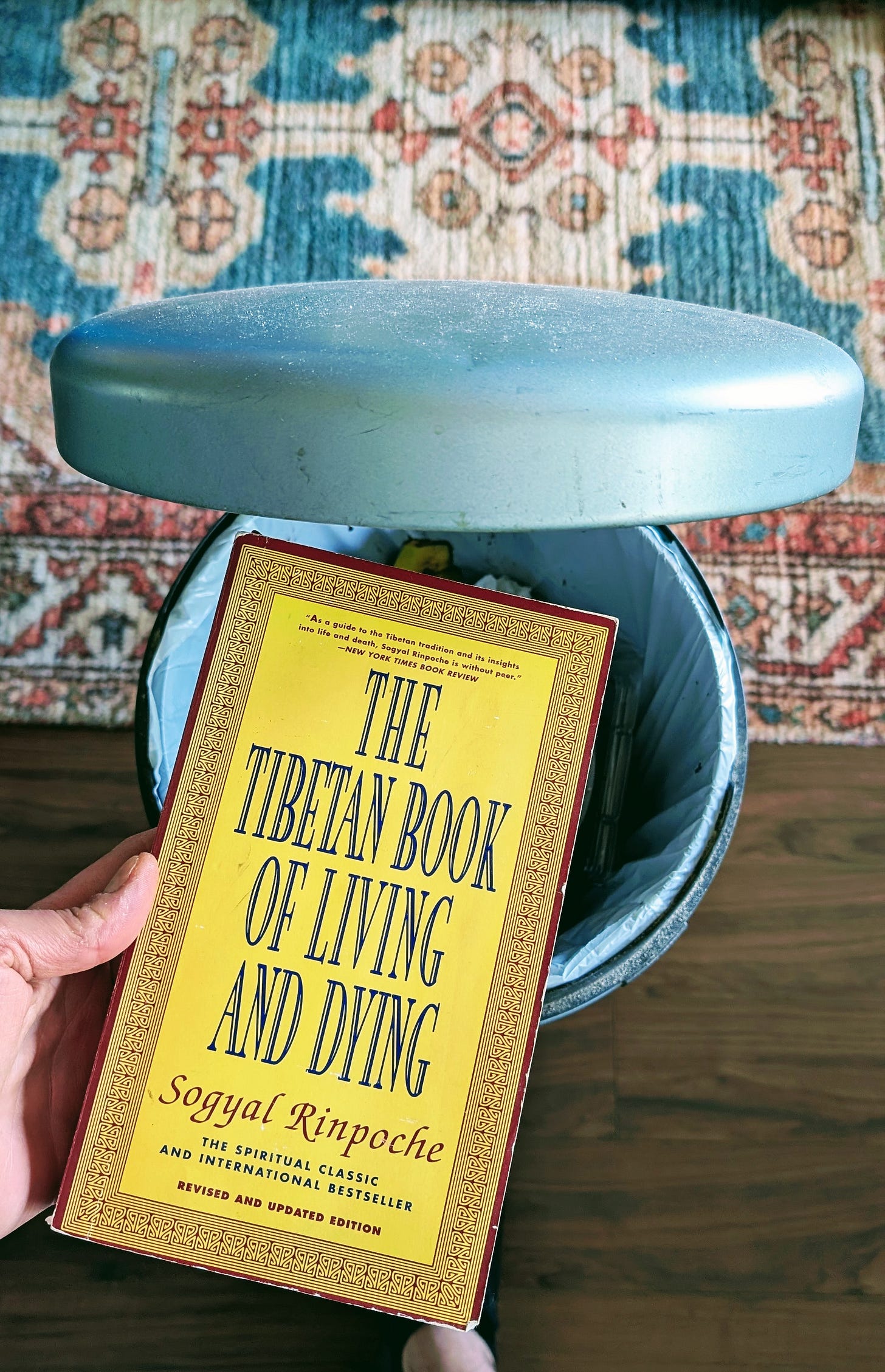

⫸ Not sure precisely where this erupted from, but enjoy… Maybe I’ve inscribed too many copies of YUCK recently with that Philip K. Dick quote:

“Symbols of the divine show up in our world initially at the trash stratum.”

In second grade, my mom started giving me money for a school lunch. Before that she made it herself, a baloney sandwich on white bread. At school I’d eat the sandwich. After school I ate the plastic bag it was wrapped in. The woman whose house I went to daycare at drove a white minivan and hidden behind the rear wheel at the back of the garage I’d crouch and tear off tiny slivers from the main body of the bag, eating as many as I could manage before the fear of being found overwhelmed me. My behavior was a source of shame, a bitter compulsion that I couldn’t control and I hid it from other children, the daycare lady, and my mother. In my mind, the baloney sandwich was the heart of my sack lunch but it could never have performed its essential duty without a plastic bag to guarantee its safe passage from kitchen cutting board to school and stomach. Ignoring the bag was impossible. At the back of the garage each day, a new sandwich bag lay hopeless in my hand—just another sack consecrated to a weekday’s doldrums, destined for the dumpster, totally unfair. The bag could not help what it was… Like every human being, I suppose, I had to pay witness to suffering or invent it to keep life interesting. But unlike many, and to my detriment, I could not watch or pretend passively. So I took swift action, or I tried to—hours after lunch, finally alone in the daycare lady’s garage, I gagged down the day’s plastic as quickly as possible, a process seldom speedy since you had to carefully roll each sliver into a tight wad then swish it in your spit. Any other way and the scraps would lodge in your throat and make you choke, a setback that necessitated a further round of retching as your fingernails scraped over the cilia of your esophagus, searching for a loose end of the unraveled bag. By the end of it all, thoroughly sapped and sickened, I used to wonder if there wasn’t another way. But it would not have been enough to simply hoard the bags, to tape them together into a raincoat or some other bricolage. There were several years when my growth in inches exceeded San Diego, California’s annual rainfall amount. My mother, too, obsessed with cleanliness, would never have tolerated my collection. Of course I could have snuck around, jammed the bags in some larger plastic sack and prayed the baloney fumes never escaped my closet. But if they did, if my mother ever discovered and opened that grocery bag, she would have seen inside it not only a nest of bacterial infection but also perhaps her son, a boy whose insides too were tangled and improperly hoarded. Better that I went on my quiet way carefully incorporating the bags into my body and being. Rising from humble synthetic origins to join the organic cycle, the bags transcended their earthly destiny, and I was brave. My living body became itself a bag, the stomach lined with impassable scraps a vessel guaranteeing the life of the lonely souls that I had invented and freed across so many solipsistic afternoons of onlychildhood.

And it was generally after one of these plastic-fueled pity parties that, disconsolate and constipated, I turned to my mantras.

Where they came from or how the ritual ever commenced, I can’t say precisely. Looking back, though, it seems they were always there, as mysterious and sudden as my own appearance in the world. Indeed, even part and parcel of it. As though included with me, like a can of paint, there came instructions for my proper disposal. The manufacturers were terse.

Who am I?

What am I?

Where am I?

Terse and rhetorical. Yet they worked. Carefully incanting the trio of demented questions on the daycare lady’s couch, before the greenish tint of her big screen TV, slowly, the feeling of separation, the certainty that I was a body with a brain and name in a certain place and time, a discreet unit of flesh and plastic independent from the crushing flux of the world’s revolving wheels, this sensation of isolated self would gradually melt away, and as it did so my anxiety would fade.

Who am I?

What am I?

Where am I?

Alongside the mantras, my own eye floaters, once I found them, became an indispensable alley in my nascent quest for ego death. At some point that year, an evening when my father didn’t show—a common occurrence whenever he planned to pick me up—I’d made the cheerful discovery staring at the TV that my cornea was covered in small clear scars, a series of tiny fissures that seemed to float like water spiders over the surface of my vision. And seated there on the daycare lady’s couch, watching them drift before the big screen as I mumbled Who am I? What am I? Where am I? the realization slowly dawned that it didn’t really matter if my dad forgot me or if he never showed his face again. It didn’t really matter either if the Jerry Springer Show was then welcoming a reluctant guest named Sandra, a transsexual, as Jerry called her, who at age thirty-five decided she was a woman, and by age fourteen had already determined she didn’t want her legs. “I didn’t want them. My brain just kept saying, ‘Get rid of em.’ So I had to get rid of ‘em.” It was easy to get rid of Sandra, to peer past the stumps hanging from the seat of her wheelchair, easy to peer past all appearances in fact—even the image of the revolving wheels of my father’s van coming to rest before another home with another child, the other son three years my senior, whom he shared with a lawfully wedded wife—easy so long as you kept intoning your mantras, knew how to find your floaters, and let the thoughts go.

Really, it was just as Master Soggy might advise: “Neither follow thoughts nor invite them; be like the ocean looking at its own waves, or the sky gazing down on the clouds that pass through it.”

Or—I might add—be like an eye staring at its own floaters.

Some afternoons the best you could do, less depressing than ingesting another hour of Disney Channel laugh track, was to cable surf south, away from those waves of toxic optimism, down to Maury, Jerry Springer, or Sally Jesse and watch your corneal cobwebs curl around the room, and wonder, as you listened to the eternal hum and bleep of the world—BLEEP! BLEEP you! You BLEEPing bastard! BLEEP sucker!!!—a world upon whose shores you found yourself so freshly thrown…

Who am I?

What am I?

Where am I?

…the eyes but two soggy non-grasping globes glinting out from the back of the living room as the broccoli started steaming, the microwave buttons beeping, the TV softly BLEEPING… And before it always the Flying Guy, my favorite floater, the one I always looked for first, a dirty little figure woven from the clear wicker of mosquito wings, his transparent twist ties twirling over the paternity test results, twitching as the teen mothers tore at their hair, flying over the airborne chairs that followed the polygraph results, the loud cheers of the makeover reveals, drifting over the shoulder of Darren, who wanted a drama free relationship, or Steve, so desperate he’d marry a horse, and Bob, who didn’t trust Regina. That’s why he watched her shower. I remember Kevin, too, a rebellious teen who went from gothic freak to gorgeous and chic. And Chiquanna, 15, who admitted to trading sex for a lobster buffet dinner. Brinkly, 17, attacked by the ants that came out of a flower.

And Chad, 27—who could ever forget poor Chad?—a sobbing dwarf who fled the stage while his lover locked mouths with another man, a fat biker, and Jerry Springer standing by acting scandalized, mumbling some cliché about the heart’s caprice as the audience cackled, others cringing as the kissing continued audibly onstage, everything set for commercial break, a few important words from our sponsors until Chad bounced back brandishing a baseball bat and started swinging for the fences, every one of his homeruns fanning the Flying Guy higher and higher until he eventually floated out of frame and the daycare lady yelled my name.

“Barret!”

Yes, there really was so much beauty in the world. Sometimes you just couldn’t bear it.

“Why are you watching such… trash!?”

But I couldn’t tell the daycare lady the truth. You simply couldn’t swallow that many bags without coming to a similar conclusion. I was trash.

And yet being trash had certain advantages, as Brinkley, Chiquanna, and Kevin could no doubt attest. People tended to look past you if you weren’t pestering anyone, paid you no more mind on a warm laissez-faire day than the broken lever on their La-Z-Boy. And reclining amidst its commodious neglect, intoning the mind’s mantras, it was possible not only to trade sex for a lobster buffet, but also to train your eye on its own weird water spiders and slowly drift away… elsewhere, into a kind of ecstasy… a place where the sad sack of self somehow ceased to exist, had proven itself more disposable than any SC Johnson Ziploc, and all the pain and worry and plastic it carried, with nothing more to protect it, dissolved wholesale suddenly, like blue pigment in that warm fluid boundlessness in which all things abide, suspended and floating, including the BLEEPing Flying Guy.

Who am I?

What am I?

Where am I?

Fuck'n weird man, I really liked it 😊👍

You should play the game, "Lisa the Painful," I think you'd enjoy it.