A Mortician's Paradise

A Dismal Errand: Part 4 + Uncanny Coincidence + Sickness + My Failed Book Project

Hate reading? Mentally challenged? Blind? Listen to this post as part of the podcast mini-series, “Expanding Erewhonian Nightmare.”

For years I’ve worked at the busiest brewery in LA. Every day I pour hundreds of beers for people from all over SoCal, the country and world. What keeps me from killing myself is the customers. Nobody ever believes I’m actually from sunny Southern California. When they hear me say “San Diego, born and raised,” they often laugh. I do not fit the mental image of the typical San Diego surf bro. They cannot picture me plopped in a hammock, joint in hand, listening to Jack Johnson. My all-black wardrobe signifies that flip flops, frisbees and fun are all allergens to shun. “You never learned to surf?” people politely probe as I pour them another pint. There must be some dark secret, a hidden injury or deformity to account for my vampiric pallor.

“I’ve seen coal miners in Iceland with deeper tans.”

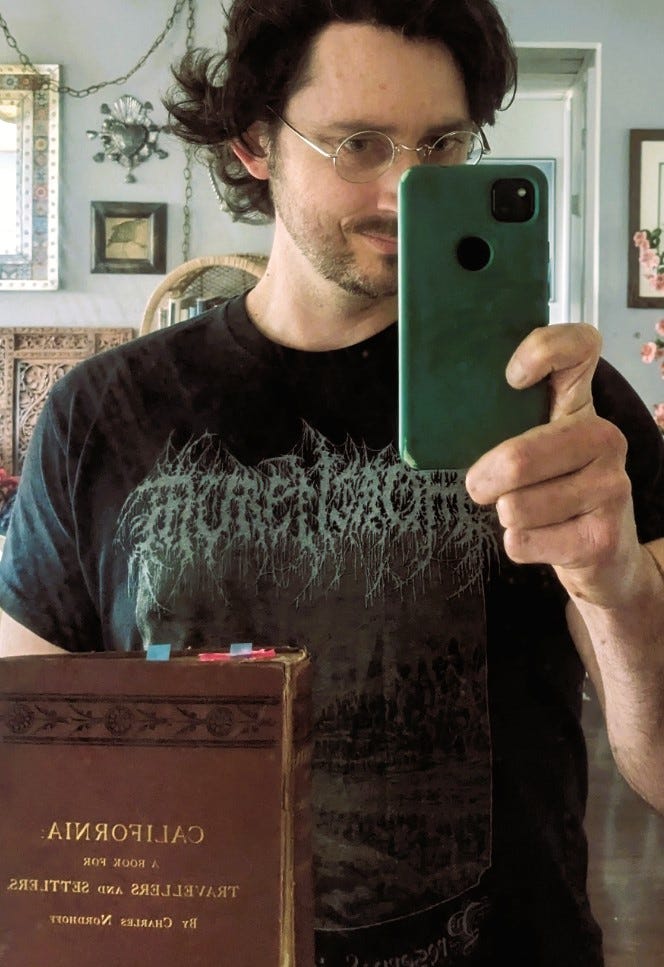

They note my shirts do not advertise the Hurley logo, but rather a chance I might hurl myself off the warehouse roof. “You really hate it here, huh?” Printed with nooses, mummified corpses, and claims like “I promise you there is enough pain” and “Preserved in Torment”, my metal shirts might appear to express the juvenile fantasy of a sudden authentic identity. Counter the conformity of sunshine, surf, and smiles with rot and torment and you can convince yourself, maybe, that you’re a cool kid.

But what not many people seem to realize is that torment and suffering used to be the mainstay in Southern California.

There is nothing more authentically SoCal than sickness and the contemplation of suicide. In fact, more people have killed themselves in Southern California than any other location on earth outside of war time. A great many of these people did hurl themselves from warehouses, cliffs, and bridges. The practice of jumping to one’s death was particularly popular in my hometown of San Diego, “America’s Finest City.” As the critic Edmond Wilson famously wrote for The New Republic in his 1931 essay, “The Jumping Off Place”:

San Diego is the extreme southwest town of the United States; and since our real westward expansion has come to a standstill, it has become a veritable jumping-off place. On the West coast today the suicide rate is twice that of the Middle Atlantic coast, and since 1911 the suicide rate of San Diego has been the highest in the United States. Between January, 1911, and January, 1927, over five hundred people killed themselves here.

San Diego, of course, had competitors. Never to be bested by its neighbor to the south, it may have in fact been Los Angeles that led the nation in self-inflected death. As Carey McWilliams recollected in 1946:

Los Angeles has always had a high suicide rate: 25.1 per 100,000 population… During the 1920s Los Angeles led the nation in the number of suicides… In the early thirties, 79 people jumped to their deaths from ‘Suicide Bridge.’ The city of Pasadena spent $20,000 a year on for a detail of policemen to guard the bridge, but the folks managed to elude them.

The same was true at San Diego’s famous Cabrillo Bridge, the famed gateway to Balboa Park. The bridge, which today spans Highway 163 near the San Diego Zoo, lacked adequate fencing and San Diegans soon began referring to it by the same name as Pasadena’s citizenry had selected for their launch pad: Suicide Bridge. A 1934 story in the San Diego Union Tribune reports that 40 people had “made the leap into eternity”—Mayor Walter Austin’s phrase—since its completion in 1915 on the eve of the Panama-California Exposition. “From San Diego there is no place else to go; you either jump into the Pacific or disappear into Mexico.”

Of course, all the action in Los Angeles and San Diego palled in comparison to the party in Santa Barbara. The most beautiful of SoCal’s resort towns, Santa Barbara was by default the best place to end it all and could boast the biggest numbers of jumpers. As John E. Baur wrote in his 1959 study, Health Seekers of Southern California:

Suicide, a notable aftermath of the quest for health, was notable in most southern California towns but became an especially lamentable problem in Santa Barbara… the city’s rate… was probably higher than anywhere else in the world.”

All of the mayhem and mutilation reads like something straight out of the song lyrics of some quality death-doom album, perhaps Mortiferum’s 2021 offering, Preserved in Torment, whose t-shirt always attracts the most attention at the brewery. Listen to Edmund Wilson list it all as the distorted drop D drones in open E:

They stuff up the cracks of their doors in the little boarding-houses that take in invalids, and turn on the gas; they go into their back sheds or back kitchens and swallow Lysol or eat ant-paste; they drive their cars into dark alleys and shoot themselves in the back seat; they hang themselves in hotel bedrooms, take overdoses of sulphonal or barbital, stab themselves with carving-knives on the municipal golf-course; or they throw themselves into the placid blue bay, where the gray battleships and cruisers of the government guard the limits of their enormous nation—already reaching out in the eighties for the sugar plantations of Honolulu.

Surfing, as you can no doubt see, is not the hallmark of Southern California authenticity. It’s really all quite astounding when you start digging into this history.

For decades, going back to the 1870s, Southern California was a “mortician’s paradise.”

All of Southern California’s initial growth, from San Diego to Redlands and Santa Barbara, was spurred by the arrival of sick people, thousands of men and women suffering from consumption who arrived in droves, driven by the sudden hope of a “magic cure”, a “climatic cure,” following the discovery of Southern California’s healthful “semi-tropical climate.”

“That Los Angeles was not bankrupted by the burden of providing medical care for transients seems to be explained by the circumstance that so many invalid tourists died shortly after their arrival,” McWilliams wrote in 1946. “One tourist of 1887 wrote to relatives in the East: ‘Should we attend the funerals of all the invalid strangers who die here, we should do little else.’”

In 1885, the editor of a Denver newspaper suggested that “the moist, warm, enervating climate of Southern California, instead of making real sanitariums, makes simply soothing death-beds for those who are beyond recovery.” Apparently, in Santa Barbara, a sign advertising “Metallic Coffins” was the first thing to greet incoming consumptives arriving by steamer. As one journalist described it, as the ship “approaches town a bell on the wharf rings out its peals; then the denizens of the place rush to the wharf. A lusty fellow yells out, ‘Another carload of consumption’… Doctors with hawklike eyes look anxiously for the poor victims that may fall into their hands.”

“A resort for the wealthy and unhealthy is all Santa Barbara aspires to now,” another reporter opined, “a pleasant place wherein to live or die.”

Coughing, it turns out, is the true soundtrack of seaside Southern California, not Jack Johnson, nor Sublime. “Most unforgettable of all the torments of the incarcerated was the constant chorus of coughing from 9pm until morning. First one occupant would have a paroxysm, then another. When the sun rose, all gathered around the sitting room fire, each telling in detail of his bad night… Consequently, most patients simply awaited the end, and in that at least they were seldom disappointed.”

As Carey Mcwilliams wrote in 1946 in his classic work, Southern California Country: An Island on the Land, “The providing of professional escorts to accompany lonely caskets back east once constituted a thriving business. Along with the intoxicating fragrance of the land there has always been the stench of decay. Los Angeles is an old town, full of death, dust, and decomposition. With houses festooned with cobwebs, reeking of decay and dry rot, parts of the city are as old as the 'fifties. Like a loathsome snake sloughing off parts of its skin, sections of Los Angeles are forever dying and rotting.” Amen, brother! Fuckin’ metal.

And if you’ve been following my last few posts about the health food store Erewhon, you may have already been anticipating my next move:

Erewhon is an absolutely insane name for a health food store headquartered in Southern California!

Southern California was literally settled by the sick. And if the logic of the fictional utopia Erewhon were applied to early Southern California, you’d have to nuke everything from Montecito down to Tijuana to keep the place clean. As I pointed out in my last post, the super-hip, psycho expensive, celebrity sprinkled LA-based wellness mecca is literally named after a fictional totalitarian Hell where the helpless and sick are purged from the earth in service of collective perfection. The society of Erewhon, portrayed in Samuel Butler’s 1872 satire, Erewhon: or, Over the Range, imprisons the sick and diseased, working them to death in concentration camps, because—in the wonderful world of Erewhon—health is something each human must own. If you are physically unwell, you are presumed to have personally failed and deserve to be jailed.

For some time now I’ve been in a unique position to appreciate the insanity of health food store named Erewhon in Southern California. For this I have only to thank my Valley Girl, Christina. Years ago, her death threats, which blocked my book about the nuclear meltdown at Santa Susana Field Laboratory in Los Angeles, led me to look for a work around. I couldn’t walk directly into the lab and write straightforward reportage. One of the first side paths I embarked on then was the history of Southern California. I had to answer the question at some point, regardless of any death threats, just how Southern California swelled into the largest interconnected built environment on earth. And more specifically, how was it exactly that the US Atomic Energy Commission thought that it would be no big deal to build an experimental nuclear reactor with no containment structure upwind from the rapidly expanding suburbs of the San Fernando Valley?

Questions related to such growth led me to look at Southern California’s origins, which, if this blog post proves anything, were rotten and diseased long before Boeing took over the nuclear meltdown site and people started dying of cancer.

The foundational text for all my research, as well as the foundational text itself for all of SoCal’s explosive growth is Charles Nordhoff’s California: For Health Pleasure and Residence. The book written in 1872, coincidentally the same year as Butler’s Erewhon, was all about how SoCal climate might cure your consumption—i.e. the same disease that everyone is condemned to prison for in Butler’s Erewhon.

“Mr. Nordhoff’s book,” wrote the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce in 1899,

has brought directly and indirectly almost as many people to this country as all that has been written since—for the thousands that originally came in consequence of that volume brought thousands of others and they again in turn many more.

Charles Nordhoff launched the Southern California utopia. There should be a monument to Nordhoff in downtown Los Angeles, but I’ve looked for it. There is none. No statue. No plaque. No commemorative gym, city park, or pedestrian square. The only thing that bears his name is a long road that runs the entire length of the San Fernando Valley. Google it. Follow it from North Hills, near Panorama City, 15 miles all the way west across the Valley.

Tell me where it leads.

Nordhoff Street, somehow, impossibly, runs straight into the Santa Susana Field Laboratory, site of largest nuclear meltdown in US history, a catastrophe that’s never been cleaned up, and the subject of my now failed book project.

Of all the tens of thousands of streets in Los Angeles County stretched over 4,000 square miles of land… It is a single street named Nordhoff that slowly crosses the Valley’s unfathomable suburban gridwork, running directly to the lab.

My work around runs right back to its own origin site, the source, the starting place: Santa Susana. An eerie, uncanny coincidence to say the least. What does it mean? How is it possible? I’ve wondered. I wonder.

Only the Chatsworth Reservoir, which the city officially closed in the ‘70s due to “seismic concerns” (in reality it was due to the radioactive and chemical waste that had run down from the hilltops) stops Nordhoff from connecting directly to Woolsey Canyon Road and running right up to the big Boeing sign at the main gates of the laboratory.

I still can't tell where you are headed with this, my friend. Conspiracy, opportunism, privilege, transition? Looking forward to your next.