Death Threats

The definitive writer's block.

In my last post, I left off at a bit of a cliff hanger...

In summer of 2018, full of grandiose illusions, I launched into what would have been my second book, a long work of investigative journalism about the largest nuclear meltdown in United States history1 only to find my path blocked by death threats.

I’d been threatened before. Once, while writing my first book, the public relations officer at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, a woman named Peggy, told me flat out, “I’m going be honest with you and ask you to respect my words. If I find out that information is published that should not be published, we’re going to put a stop to you.” Before that I met a nice girl in graduate school. “If you ever even think of writing about me, I’ll tell everyone about your micropenis.” And there was Christina, too, her continual refrain back in the day. “You just want to render me in fiction.”

“Worse!” I used to call after her bike, never certain if she’d answer my texts again. “Nonfiction!” But as far as I knew, up until the summer of 2018, no one—except for my mother—had ever threatened my life.

The threats, when they started, were both terrifying and titillating and I took them to mean that I was on the right track. Certainly it isn’t every day that you embark on a book about a patch of land owned by a little $122 billion company called Boeing only to find it communicated, in no uncertain terms, that if you continue any further along the road upon which your research is heading you will be killed.

That road, as it turns out, has a name. Woolsey it’s called. Woolsey Canyon Road. And a fair amount of people actually die on it. It isn’t their desire to expose the largest nuclear meltdown in United States history that does them in so much as bad brakes, or booze. Other times it’s the view.

The road rises eight-hundred feet from the far west end of the San Fernando Valley to the top of the Simi Hills, a narrow ribbon of battered asphalt burrowing into the western border wall of LA County, and on a clear day, as the view unfurls behind you—the entirety of the Valley’s 235-square mile gridwork stretched out below like some monolithic printed circuit board, the blinking diodes of its roads, the humming transistors and resistors of its homes, strip malls and hospitals rippling in a haze of heat as the one program our species can never unplug, Growth, runs on unsupervised toward oblivion—it’s hard sometimes, rowing the steering wheel round the bend, not to want to continue straight off the cliff.

But I managed to be a good boy that summer, to stay mostly sane, and stay on the road. It was only in appearance that I’d made the catastrophic mistake of moving to Los Angeles.

In reality, the megatropolis was just an ephemeral little fling, a tryst with dystopia that would yield much bigger things. Not more subdivisions of course, but a contract with a subsidiary of Knopf, and perhaps a long run in Oprah’s Book Club, assuming I could keep it all simple, forget about W.G. Sebald, and give it the old Erin Brockovich rub. Yes, a story about kids fighting the cancer caused by corporate greed. You’d have to work really hard to fuck it all up.

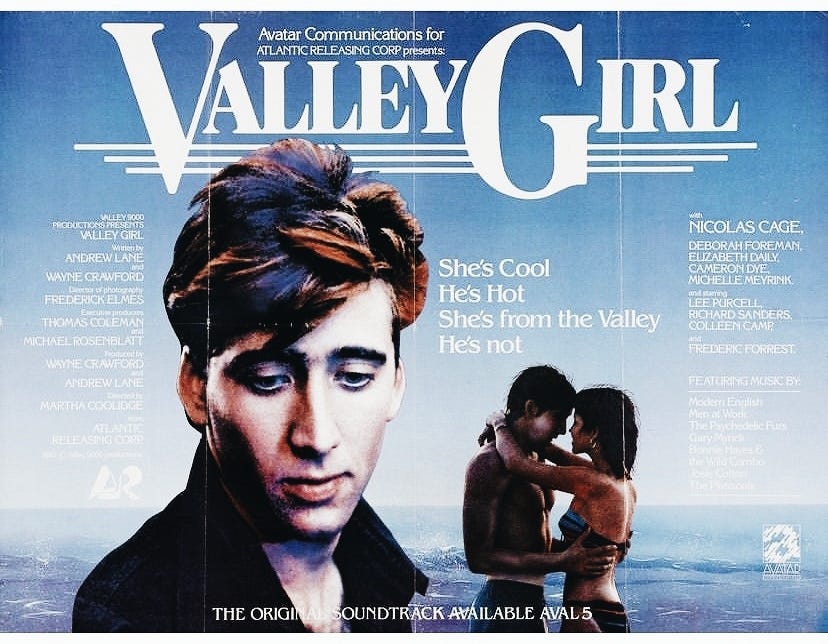

As my one-time Valley Girl, Christina, told me early that summer:

“Your book could be… like… really big…”

I thought it would be nice to have something big attached to me.

But one hot, steamy summer’s day, high above the Valley, something forced me from that simple, straightforward road of common sense, mass market narrative nonfiction.