Rain Falls When a Mountain Sheep is Killed

Shamanism, Climate Intervention, and Uncanny Coincidence in the Mojave Desert (The Heights of Weird Part 4)

“Symbols of the divine show up in our world initially at the trash stratum.” —Philip K. Dick

I got a nice comment from a reader named Nick in response to my last post.

“It’s a tragedy that the way, extent and degree of depth you’re writing is utterly, vastly, completely out of whack with 99% of what is written on Substack, where the 3 paragraph puff pieces by 25-year-old women talking about how they shared a muffin with their dog, and being happy with themselves, get 300 comments.” So true!

I want to start off first by saying thanks for the support, Nick. I truly love hearing from fans other than my Trumpy uncle.

That said, I am a firm believer that there’s nothing wrong with muffins or puff. Sometimes little soothes the soul quite like a half-full snack-size Ruffles bag worth of words that savor of the most vapid form of nothing. It can feel good to comment on them too! And it doesn’t matter if you’re a 26-year-old male incel selling crypto secrets to unemployed ‘entrepreneurs’ or a female senior researcher at JPL who just happens to derive joy from the little, local things in life. As long as you give it your all and do the goodest job as you know you can do, that’s what this is about. For you, of course. But not me.

Nick is right—I’m in the business of tragedy.

So let’s get down to it, now that I’ve already exceeded the average length of 99% of successful posts on Substack.

What weird shit did I wander into back in 2013? How is it still reverberating through my veins? What lay at the far shore of that Google search I left off with in my last post?

Further, how does the weird shit connect to this blog and the failed book project I keep blabbing on about, the one about the nuclear meltdown at the Santa Susana Field Laboratory, the largest nuclear meltdown in American history, a disaster that happened right here in Los Angeles beyond the Olive Garden, the Starbucks, and suburban backyards at the end of the Valley—indeed, right behind Christina’s mom’s house—and that’s given thousands of people cancer, never been cleaned up, and basically no one’s heard of?

Except Kim Kardashian.

I might as well come out with it. Or perhaps I’ll let one of the world’s top climate scientists, Stanford’s Ken Caldeira, do the honors:

“Is there more to it then irony?”

These were the words Caldeira asked me when I carried my extremely weird shit to his Stanford lab exactly one (fuck my life) decade ago, in July 2014.

My path to Ken’s lab had started the year before in September 2013 on that dismal morning I portrayed in my last post, when, horrifically hungover in Iowa, my pinky finger hovered over the keyboard, poised to fire off a fateful Google search:

China Lake petroglyphs meaning

As I wrote about in that post, “Scratching the Surface,” I had randomly begun digging into something called ‘cloud seeding’ that morning in September 2013, a weather modification technology that sounded at first blush like total bullshit conspiracy. Yet, hard as it was to believe, the US government had for decades studied how to manufacture more ferocious rainstorms, research that led to the highly classified deployment of cloud seeding as a weather weapon during the Vietnam War in a five-year operation known as Project Popeye.

I remember my thought that morning in Iowa, sitting there horrifically hungover, staring at my laptop… Fuck, if the US government was obsessed with hacking the weather as far back as the 1950s, they gotta have some way crazy shit in place to screw with the climate today.

I was not wrong.

As I’d already quickly gathered that morning, going as far back as the 1960s when the greenhouse effect was first gaining widespread scientific acceptance, the US government had been advocating for “the possibility of deliberately bringing about countervailing climatic changes.” (See a prior post, “Solar Geoengineering and Santa Susana.”) One of the primary early proponents for hacking the global climate system to counteract the greenhouse effect was none other than Edward Teller, father of the hydrogen bomb. “The Planet Needs a Sunscreen” Teller titled a 1998 Wall Street Journal op-ed, describing the idea of partially blocking out the sun to artificially cool the planet—a climate intervention strategy better known as solar geoengineering or solar radiation management (SRM)—as “not a new concept, and certainly not a complex one.” So true, Eddie! Easy as eatin’ a muffin!

Yes, the simple solution to indefinite economic growth via the unabated combustion of cheap, affordable fossil fuels formerly sequestered in the earth’s dark chthonic depths for untold eons was. . . no big deal. . . carry on business as usual. Be happy with yourself! Just make sure you’re continually mimicking a large-scale volcanic eruption by injecting millions of tons of light-scattering toxic sulfur aerosol puff deep into the stratosphere from a dozen retrofitted Boeing 747s circling the earth’s equator forever.

It was and still is a proposal that sounds a lot like chemtrails, which, if you haven’t lurked long on any gloomy conspiracy blogs full of blurry slides and—like this crappy Substack—urgent calls to subscribe and even donate, you might not know remain at the root of all mortal affliction.

And that very morning, just as the dismal discovery1 of solar geoengineering began streaming through my dying Dell laptop, the media was reporting that the release of the first third of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) massive Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) was only days away. Lines from the ‘Summary for Policy Makers’ had already leaked. “Warming of the climate system is unequivocal,” the IPCC concluded for the very first time, “and since the 1950s, many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia.”

It was amidst these dire reports and unproven proposals, toggling between talk of turning the sky white and the current pace of warming exceeding the Permian-Triassic Extinction Event, aka ‘the Great Dying,’ that my fateful Google search eventually fell upon the name of Stanford’s Ken Caldeira.

Caldeira, along with Harvard’s David Keith, ran FICER—The Fund for Innovative Climate and Energy Research. At that time the company had received almost $5 million from Bill Gates to conduct its research, all of which had taken place indoors on computer models. Supposedly, no solar radiation management field tests had yet been conducted. But Caldeira and Keith thought this ought to change.

As Caldeira testified before Congress in 2009, “it is probably already too late for us to see the Earth start to cool this century. . . In every emissions scenario considered by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, temperatures continue to increase throughout this century.”

Caldeira’s testimony continued:

“What if we were to find out that parts of Greenland were sliding into the sea, and that sea-level might rise 10 feet by mid-century? What if rainfall patterns shifted in a way that caused massive famines? What if our agricultural heartland turned into a perpetual dustbowl? And what if research told us that an appropriate placement of tiny particles in the stratosphere could reverse all or some of these effects?”

Caldeira abandoned the sunscreen analogy in favor of seatbelts. Unlike Edward Teller, he sounded conscious of and much less confident about the unintended side-effects of such a brute-force intervention in the global climate system.

“We do not want our seatbelts to be tested for the first time when we are in an automobile accident. If the seatbelts are not going to work, it would be good to know that now. If there is something really wrong with thoughtfully intervening in the climate system, we should try to find that out now, so that if a crisis occurs, policy makers are not put in the [position] of having to decide whether to let people die or try to save their lives by deploying, at full scale, an untested system.”

Incredibly, in response to the arguments of elite scientists like Caldeira and David Keith, exactly two months earlier, on July 17, 2013, the CIA had begun quietly funding a 21-month study conducted by the National Academy of Sciences into the various technological means by which human beings might ‘thoughtfully intervene’ in the event of a global climate emergency.

A thought occurred to me that morning as I struggled to digest all this epic shit:

I wonder if the US government is studying solar geoengineering at China Lake?

Recall that the above sudden barrage of doomsday research kicked off for me that morning of September 17, 2013, only after clicking randomly on some conspiracy blog a Facebook friend posted as news and coming across there the deranged claim that the recent and truly Biblical floods that decimated Colorado days before had been created by the US government intentionally via cloud seeding.

Despite the apparent insanity of such a theory, three items remained beyond doubt 1) the US military had for decades sought a weather modification weapon 2) the revelation of its actual years-long deployment in Vietnam had sufficiently spooked the international community as to trigger a United Nations Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques (ENMOD), and 3) the development of this weapon had taken place at a secretive California desert military base, i.e. China Lake.

A conclusion forced itself on me. Of course the United States was aggressively pursuing research into solar geoengineering; current US security policy and doctrine would never permit any other nation or group to operate such a system. And the research was, of course, taking place at China Lake.

“We regard the weather as a weapon. Anything one can use to get his way is a weapon and the weather is as good a one as any.” —Dr. Pierre Saint Amand, Geophysicist, NWC China Lake

And yet none of this was the weird shit I carried to Ken Caldeira at his Stanford lab in the summer of 2014. No, this was all just information. Trivia. Still surface level stuff. And reading it all that morning horrifically hungover, I kept hearing the maddening refrain of my mentor, John D’Agata: “Go—”

“Deeper”

“Deeper”

“Deeper”

“Deeper”

“Deeper”

“Deeper”

“Is there anything more to it than irony?”

—Ken Caldeira, Senior Staff Scientist (emeritus) in the Carnegie Institution for Science’s Department of Global Ecology, and Professor (by courtesy) in the Stanford University Department of Earth System Sciences, to the unknown failed writer Barret Baumgart, who thought, as the two strolled across the Stanford campus in the summer of 2014, that Caldeira walked like any man might if forced to bear some portion of total human failure; he looked like the author’s stepfather except his back was a bit more bent, his thinning hair fizzed out a little farther, and when he stood the slight hunch kept his gaze focused on the sidewalk two feet in front of his sandals instead of six; the author supposed, at first, that his body had simply adapted itself to long hours crouched over keyboards while supercomputers cranked out their month-long climate models, but it seemed an odd posture, especially for someone supposedly studying how to inject sulfur aerosols 100,000 feet into the stratosphere, but Caldeira occasionally glanced up, and when he did his grin was mostly warm and his words rang calm, yet still you could see inside his eyes that his mind never stopped working, and while Caldeira and the author walked across the Stanford campus, while the former kept his fingers clasped behind his back in thoughtful professor pose, the latter couldn’t help thinking the entire time that he looked like a prisoner in handcuffs.

“I was hoping you could tell me.”

It was Friday. Caldeira had dressed casually. A salmon-colored Tommy Bahama button down, faded blue jeans, and leather sandals. He camouflaged well with Stanford’s sunny Spanish Colonial architecture, the geometrical stands of palm trees, the general privileged, monastic calm that permeates one of the world’s top research institutions.2

“Hmm,” Caldeira said. “Well primitive cultures were always concerned with modifying the weather…”

The essence of irony rests in a discrepancy between what one expects and what one finds. When you FaceTime me on a sunny Sunday morning and ask, “How are you, Blarry!?” and staring out the window as the flames of a raging dumpster eat the sparks out of popping power lines, I say, “I’m living the dream,” I am exercising my right to irony. In a safe, well-constructed world free from catastrophe and cowardice, you would not expect someone to characterize such a snafu as the zenith of human achievement. The statement is ironic.

As irony relates to only the beginning of the psycho weird shit I’m still taking longer than 99% of Substack writers to cough up…

It was of course ironic that the US military chose to research cloud seeding at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake. Why the hell would the US military concentrate all their weird rainmaking research deep in California’s Mojave Desert, beside Death Valley, the driest place in North America and the hottest place on earth?

One would not expect to find the epicenter of weather modification in a place utterly devoid of that which one sought to modify.

(That is unless the military, hoping to at last harness the supernatural power of the earth, found recourse to resort to the type of symbolic inversions common throughout the Native American societies it once actively erased.)

It was ironic, too, that I’d stumbled upon this bizarre weather—and now climate—modification history in late 2013, at the height of the worst drought on record in the west, and just as the first-ever state-wide water restrictions were kicking in across California.

Ironic, too, that Pierre Saint Amand, the man behind China Lake’s decades-long cloud seeding research (“Mr. Chairman, distinguished Senators, and guests: My name is Pierre Saint Amand; I live at 112 Blueridge, China Lake, California) had almost anticipated this moment in his top-secret testimony before Congress in the 1970s:

“We are now engaged in study of a technique for slowing down portions of winter storms and thus changing their trajectory so that the rain along the Pacific coast of California might be spread out a little more equitably thus reducing the perennial drought in Southern California…”

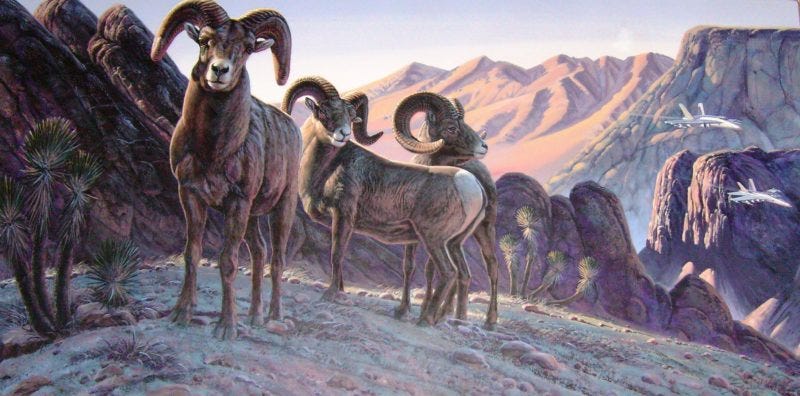

It was ironic, too, of course, that NAWS China Lake, perhaps the US military’s most advanced weapons research center, was home to the largest concentration of ancient Native American rock art in the Western Hemisphere. A single narrow lava canyon alone held perhaps 1 million-plus petroglyphs, most of them depicting bighorn sheep. Some of these images dated back as far as 16,000 years, making them the oldest known rock art in the Americas.

And the military was committed to protecting it all. (“NAWS China Lake aggressively pursues site protection…” “Everything in the canyon area is fully protected…”)

How ironic to find a facility dedicated to discovering future ways of wiping humans off the planet committed unconditionally to preserving the artwork of their past.

“Irony is the song of the prisoner who’s come to love his cage.” —David Foster Wallace

But what was NOT ironic was the weird shit I brought to Ken Caldeira at Stanford, the same eerie stuff that forced me to start China Lake in the first place and worry later on, silently, at the far shore of that fateful Google search, what it was I’d actually wandered into…

It’s thought that China Lake’s cloud seeding research first began in 1949. This date, however, is misleading. Weather modification research actually began at China Lake much earlier. The Navy says that China Lake has remained “one of the preeminent research, development, test and evaluation institutions in the world for more than 60 years.” Paul Wolfowitz says that China Lake has “produced some of the most remarkable technological breakthroughs” and that the base’s flexibility in management “has allowed us to keep the very best people around.”

But who are the very best people? The Navy acknowledges the antiquity of the petroglyphs and protects them as an invaluable cultural resource, but nobody understands their meaning.

The lava canyons of the Coso Range—situated within the bounds of NAWS China Lake—formed the central pilgrimage point for rainmaking shamans throughout the American west for 15,000 years.

“A dream of mountain sheep gives power.”

“A mountain sheep singer always dreamed of rain, a bull-roarer and quail tufted cap of mountain sheep hide.”

“Wooden bull-roarers were toys, but those of mountain sheep horns were for rainmaking.”

“It is said that rain falls when a mountain sheep is killed. For this reason many sheep-dreamers thought they were rain doctors.”

The US military and ancient Native Americans chose the same location to modify the weather. It hadn’t worked out for either.

That was why I had traveled to Standford. I wanted to tell Caldeira what I had learned. The discovery that I had made. Something so fucking weird and improbable and strange, and that no one else on the planet had yet perceived, that its grand and isolated oddity gave me, a dumb ass dude from San Diego with no institutional backing, no book deal, press credentials or important contacts, the courage and arrogance to travel to Stanford, the bowels of the Pentagon, and the creepy canyons of a secret military base stashed away in the Mojave Desert, all the while seeking out, stalking, and talking at length to some the world’s top scientists and archaeologists.

It was not in instance of irony, but something other—an unsettling coincidence, an uncanny coincidence. And for me, dare I confess it… a meaningful one? Loathe as I am today to deploy a word infused with so much hackneyed New Age woo, the coincidence was precisely that which the Nobel Prize-winning quantum physicist Wolfgang Pauli termed, alongside psychologist Carl Jung in a now famous 1952 paper, an instance of synchronicity.

What the hell did it mean? I had no idea. In all probability nothing.

“The historical and cultural foundations of the Nation should be preserved”—says NAWS China Lake—“as a living part of our community life and development in order to give a sense of orientation to the American people.”

Or better yet: disorientation.

How was such a coincidence possible? And how was I the one to stumble on it—especially after all the unpromising stops and starts I belabored in my last post?

As renowned archaeologist David Whitley told me the very next day, after I left Ken Caldeira’s Standford lab, “It’s really freakin’ weird.”

Weird does seem like the right word. It is an old, an ancient term, originally wyrd, meaning fate, chance, destiny. Or literally, “that which comes.”

“It’s not ironic,” David Whitley insisted. “It’s just weird.” Whitley was the first American allowed inside Chauvet Cave following its discovery in France in 1994. He was the one who had figured out the China Lake rock art was likely not sympathetic hunting magic but an attempt at rainmaking. Apparently, he was the only archaeologist who’d ever read the statements of actual Indians. “It’s all in the ethnography,” he told me. “Trouble is nobody will read it.”3

weird (adj.)

c. 1400, “having power to control fate,” from wierd (n.), from Old English wyrd “fate, chance, fortune; destiny; the Fates,” literally “that which comes…” —Online Etymology Dictionary

I had no reason to believe anything more was coming after that summer. Probably I wouldn’t have thought any more about coincidence. I never would have typed out that hollow bludgeon of the self-help gurus, “synchronicity,” as I did just now above. And after typing up China Lake and mailing it off in April 2015, I probably would not have ever thought much more about Native American rock art. After spending 18-months writing about blocking out the sun with sulfuric acid, I needed a vacation. A clean, well-lighted place to sit down and meditate on a possible lobotomy.

But David Whitley told me another thing.

We’d spent the day hiking north of NAWS China Lake, searching for bighorn petroglyphs. The rock art there was unprotected, beyond the base’s barbed wire, and susceptible to vandals. At some point I asked David if there was any Native American rock art in some super shitty spot. Like in Southern California, hiding out in the suburbs on some boulder behind Starbucks.

To my surprise, David Whitley said yes.

There was a site somewhere in Los Angeles, or maybe it was Ventura County. He couldn’t remember the exact location. But it was at the end of the Valley. Someone had been carrying a Geiger counter the one time he’d been out there briefly to consult.

“It wouldn’t stop clicking.”

I didn’t think much of Whitley’s story at the time. I had long ago vowed never to set foot in the San Fernando Valley, so whatever rock art was out there would be forever dead to me. Yet six months later, reluctantly, and after much coaxing, I drove up to meet Christina’s family for Christmas. And somehow I didn’t leave.

I remember the colors overhead as I fought to finish China Lake each night, adjusting the broken blinds in the spare bedroom, tacking up towels and my black metal t-shirts, and cracking too many of Christina’s stepdad’s Modelos. They were often unsettling. That was supposed to be one of the side effects of solar geoengineering: blood red sunsets that lasted too long.

And the side effect of my earlier “synchronicity”?

Unbeknownst to me, just beyond the backyard, it was nothing other than the arid irradiated hills of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory that the western sun set behind each of those eerie red evenings.

Click, click. Click.

→ Read Part 5 of this Series

The first thing I found that really blew my mind, my first introduction to the idea of solar geoengineering, was this insane essay in The Wilson Quarterly, “The Climate Engineers,” by Dr. James Rodger Fleming, Professor Emeritus of Science, Technology, and Society at Colby College, and author of Fixing the Sky.

Several sections of this post poach pages and paragraphs from my YA lesbian vampire novel, China Lake: A Journey into the Contradicted Heart of a Global Climate Catastrophe.

David Whitley quoted in China Lake. “White college-educated archaeologists felt little need to talk to Indians or read their statements. When they occasionally tried and found that Native American informants couldn’t prove their theory, they simply assumed that the Indians had no idea what they were talking about.” For the bighorn sheep/rainmaking connection, see David Whitley’s 1994 essay, “By the Hunter, For the Gatherer: art, social relations and subsistence change in the prehistoric Great Basin,” and his 1998 work, “Cognitive Neuroscience, Shamanism and the Rock Art of Native California.” A profound and mind-expanding read on shamanism, prehistoric rock art, and the origins of human creativity can be found in David Whitley’s 2010 book Cave Paintings and the Human Spirit. A TED Talk with Whitley is here.

For a deeper dive on the rock art of the Coso Range, see China Lake pages 6-7, 43-97 117-120, 148-155, and 222-242.

For more on protecting the rock art and supporting the Native American communities for whom it is sacred, read my post “A Festival of Theft.”

Love this Barret. So fascinating, well written & researched per usual. If I knew anything about the computer internet I’d hack this blog and delete your self deprecating comments. Keep going.

CHINA LAKE

China Lake

China. Lake.

It’s interesting to note that the geoengineering theme was fully present in Isaac Asimov’s books, in both the Foundation and Robot multi novel epics, from an early point, to the early 50s. He had fully envisioned planets covered by temperature controlled domes, and the mega city planet of Trantor so paved over in every direction, that cats were now found in zoos, as one of the main attractions. In the Robot books, detective Elijah Bailey becomes an unlikely proponent of “naturally” going back to the outside, leaving the domes, and experiencing planting stuff again, even as the lack of a closed in surface makes him uneasy, like all dome dwellers, and he is thought of derisively, as an absurd eccentrist for engaging in the Outside, something normally only for robots ploughing fields and as horrible punishments for exiles (something not different to how Chinese intellectuals were treated in the Tang dynasty, in a pre-technological era). Of course, unlike many technologists today, Asimov was an environmentalist, even though he was a notorious ass slapper. Kind of like how Brave New World was actually a satire of how unironically terrifying American values were even 100 years ago, but Americans have since appropriated the terms “Alpha” and “Beta” from it, unironically, completely missing the point. What would Mr DFW say if he was still with us?