This is the end. It’s taken me years to force myself to write this. The coincidence revealed below is a frightening, gorgeous world-historic fact of uncanny import, and all the more shocking when viewed in light of the prior “Weird” posts. It is also only the tip of the iceberg. But rest assured, the visible peak is cutting.

“But enough!” you say. “Shut up! What is it?”

This is the catalyst, the beginning of the blood flow. This is the unsettling sequel to China Lake. This is why I quit drinking and Googled coincidence. I haven’t had a sip of booze in over 30 months. This is the start of my third book. Here I follow through on what I pledged to do in my first post in this series “The Heights of Weird.”

In that first post I wrote A) My failed book project about the nuclear meltdown at Santa Susana was a sequel to China Lake B) The two were, and are, fatefully, fundamentally, and ferociously tied. But how? C) Hint: It’s really weird.

“But enough” you say. “Seriously! Shut the fuck up!” Okay.

Admittedly, writing 25,000 words over 7 months after avoiding the task for years in a psychotic gambit to jump start your dead book project about America’s largest nuclear meltdown is probably not how you’re supposed to use Substack.

My new year’s resolution is to finally get my shit together and start posting proper 300 to 400-word puff pieces each week about muffins and puppies.

Wish me luck!

The below picks up roughly where the last post, “The Tower of Rot,” left off.

If you want to listen to the series, a pretty convincing A.I. voice will read each post for you if you open it in the Substack mobile app and click the play ▶️ button at the top right. I will also render them in my sultry barretone in podcast episodes coming soon.

“I think the most important question facing humanity is, ‘Is the universe a friendly place?’ This is the first and most basic question all people must answer for themselves.” —Einstein

“Santa Susana Field Laboratory rock art” I typed into a tab on the dying Dell laptop…

It took me a minute to realize I’d been Google-jacked, the engine’s predictive algorithm overriding my search with an evidently more popular term, not ‘rock art’ but rocket. “Santa Susana Rocket.” But what I started reading was intriguing…

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL) had not just done nuclear research, Wikipedia said. No doubt an estimated 10 experimental nuclear reactors operated at the facility between 1953 and 1980—“It was my impression that Atomics International had been given verbal instructions from the Atomic Energy Commission to test the reactor to destruction,” one former SSFL employee was quoted as saying. “They were pushing the limits on purpose.”

Yet the field lab’s primary mission—more critical than creating nuclear meltdowns—was rocket research.

And SSFL wasn’t just any average rocket research center, if such a thing existed. Rather it was “the most gigantic rocket engine workshop in the western hemisphere.” Around 30,000 rocket engine tests were conducted at Santa Susana between 1949 and 2006. Most of these tests took place on Area II of the laboratory, a crucial 400-acre cross section of the 2,800-acre lab home to a series of towering “static” rocket test stands bolted into the bedrock.

The first rocket engines SSFL workers ever anchored to Area II’s monolithic sky-scraping frames were, incredibly, Nazi V-2 “Vengeance” rockets. In fact, the quiet dismantling and analyzing of German V-2s above the expanding suburbs of the San Fernando Valley was the very first project undertaken at Santa Susana in 1947, or so the internet said.

V-2 plans and the personnel that built them, including the notorious rocket scientist Wernher Von Braun, had been smuggled out of Nazi Germany in 1945 under a now infamous top-secret US intelligence operation codenamed “Paperclip” and brought to none other than the Santa Susana Field Laboratory at the end of the Valley. Nazi scientists were instrumental in the selection of the Santa Susana site, whose rocky topography, so I read, apparently mirrored underground Nazi test facilities at Nordhausen and the Lehesten quarry site throughout 1944-1945. Santa Susana’s natural rock bowls formed perfect “flame buckets” that deflected rocket exhaust away from test stands and later diverted coolant chemicals into drainage ditches.

Sidebar: The primary drainage ditch at Santa Susana was, historically, the Los Angeles River, whose headwaters begin—literally, actually—in the irradiated hills of SSFL, flowing down off the lab into the gated subdivision of Bell Canyon, near Hidden Hills, the home of Kim Kardashian, before following the flood control channels made famous in Terminator 2 and continuing onward through the Valley, Downtown LA, and Long Beach, briefly passing Terminal Island… before spilling out to sea.

“This is a great illustration of why this area was selected,” said Peter Zorba, a NASA project director. “It gave the United States government a head start…”

I remember at some point, somewhere around the talk of Nazis and natural rock bowls, I stopped reading. It was pretty radical information, not really what I anticipated after several years of staunch dismissal of SSFL. I sat there on the yoga ball thinking and listening as, at the south end of the alley, the collective sob of five hundred food animals imprisoned inside LA Fresh Poultry spattered the air with their abattoir babel. Cluk-Cluk-Cluk-Cluk, Kli-Kli-Kli-Kli-Kli. Cluk-Cluk-Cluk-Cluk, Kli-Kli-Kli-Kli-Kli-Kli-Kli. A car door slam cut through the threnody. Cluk-Cluk-Cluk-Cluk, Kli-Kli-Kli-Kli. Klok.

I stood and crossed toward the window.

There was a van parked in the driveway between the alley and Virgil Avenue. A black sprinter van. A tall halal order was being fulfilled. The bird population always boomed before Jesus’s birthday, and I remember watching one of the butchers, a cheerless Egyptian in rubber coveralls, lugging bag after bag of bled and plucked birds out to the back of the Benz.

“Dieciséis! Dieciséis!” The hysterical, amplified cries of bingo numbers pierced through the wall of banda tubas blubbering out back. Were the pretty, young Latina attendees teaching the senile grandmothers from Estonia Español? I never fucking knew. “Trece!” they called through the big peavy speakers. “Trece!”

Thirteen, I thought, lucky number thirteen.

A downy white feather drifted past the window, more the product probably of a chucked comforter than twitching chickens. I watched it float for a moment, fibers incandescent, like a dandelion seed. I made no wish. There was no epiphany fluttering at the edge of my perception. No premonition of the miraculous or especially disastrous. Little to suggest any form of high weirdness worming my way in that turmoil of wings and tortured bird screams. I remember watching another blank bag disappear into the back of that black sprinter van. The tepid conviction that I shouldn’t eat chicken filtered through my mind for the eight hundredth time. “Nueve! Nueve!”

I turned from the window and sat down again on the yoga ball before the dying Dell laptop. “Cuatro! Cuatro!” Part of me wanted to call it an afternoon, hike up to the Monte Carlo. Happy hour was fast approaching, and I was thirsty. I could always circle back to my rock art-rocket research. What was the rush? There was obviously nothing there. Don’t let von Braun and Nazi secrets distract you from the catastrophic emptiness of Los Angeles. But seeing that photo framed at the head of my bed—an image of perfect horse and rhino heads painted inside Chauvet Cave by shamans 36,000 years before the present dismal moment—I felt determined to go on, get it over with.

The rocket stuff was obviously weird, but there was no way the rock art could amount to much. Not in Los Angeles. Not at the end of the Valley.

Yet somewhere in the back of my mind, behind the manic flatulence of the banda brass, I heard a voice swim up through the din. It didn’t sound enraged, drug addicted, or hopelessly insane, and I knew at once it must be Montaigne. Calm and clear were the words.

Que sais-je?

“What do I know? What do I really know?”

Flicking the mouse, the story of SSFL’s site selection continued: “They were able to use the geology and the rock outcrops for natural revetments and drainages,” said NASA’s Peter Zorba. “They didn’t have to spend millions of dollars and millions of hours constructing drainage and revetments.”

The readily accessible headlands of the Valley, only a 35-minute drive from CalTech and prefabbed with natural sandstone flame buckets, made Santa Susana the most important rocket test lab in the world, both for nuclear armed ICBMs and the biggest manned rockets ever built.

As NASA’s Ray Tjulander put it, “It has been the major rocket engine test site in this country; there is no question about it.”

I clicked to another Los Angeles Times article. “Since 1947,” it read, “the engines for almost every American rocket program came to life for the first time amid the sandstone and sage of these rough mountains.” Indeed, the initial testing of the F-1 and J-2 rocket engines that powered the Apollo missions took place at SSFL.

From 1964 to 1968, “the most active period,” according to NASA documents, “nearly all Saturn V testing took place at the large Coca I and Coca IV stands.”

Saturn V was, of course, the rocket which launched man to the moon in July 1969.

Wernher Von Braun was chief architect of the 36-story Saturn V rocket, a mechanical marvel three heads taller than the Statue of Liberty. Work upon the unfathomable Saturn V began immediately following President John F. Kennedy’s special address to congress in May 1961 and progressed at an astonishing pace—even without the enslaved labor von Braun and his compatriots formerly enjoyed from the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp.

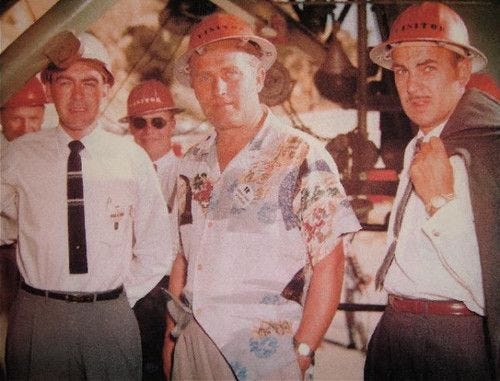

“Wernher von Braun used to stand where I am standing now,” a rocket engineer, one Arnie Sodegren, was quoted in another old Times article. “All around him would be engineers checking instruments, looking out the windows, waiting to see what would happen.” According to Sodergren,

“This is a place of history… You could say that right here is where space exploration began in this country.”

There was that day a fierce debate brewing over the laboratory’s history. Nobody seemed to mind too much that 1,600 unrepentant Nazis were brought to the United States after the war, given great salaries, and put in charge of America’s most sensitive military and aerospace programs. The debate raged, rather, around the rocket test stands at Santa Susana, especially the biggest among them—the two main Coca stands at NASA’s Area II that performed nearly all the Saturn V testing.

“NASA and the Air Force… simply have no historical consciousness,” another article quoted Harry Butowsky, a professor. “They’re only interested in the future, and what they’re going to do. They have no interest in their history at all.” Butowsky referred to Santa Susana, whose giant test stands NASA apparently planned to demolish. SSFL is “the best remaining example of this large infrastructure that we had in place that took us to the moon,” said Butowsky, a former National Parks historian.

I remember thinking, What the fuck? Are people trying to turn this irradiated hellhole into a US National Park? The word UNESCO dotted several of the articles. Even NASA, apparently, was looking into the possibility. There was some talk on the table of a National Monument named Sky Valley.

All that for some rusted rocket stands built by Nazis?

“We believe… any demolition of the rocket test stands, especially Coca, should be deferred for as long as possible so as to maximize its chances of being protected as an integral part of any SSFL National Monument,” wrote Vincent Armenta, chairman of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash. WTF? Why did Native Americans give a shit about some heaps of metal with a name one-half of Coca-Cola?

Even Dr. Ed Krupp, director of the Griffith Observatory, which I hiked past every week—if I didn’t drink too many IPAs—was pushing NASA to save those towering, toxic metal monsters hiding in the hills at the head of the Valley. Santa Susana “is irreplaceably significant in the history of space exploration,” Krupp wrote, “the history of NASA, the history of California and America, and the history of the world.”

Clark Stevens, an architect working on plans for the proposed “Sky Valley” National Monument went further:

“This 2,800-acre plateau, now the Santa Susana Field Lab, and perhaps one day to be open space protected from development, was and is the place where cosmic order is revealed.”

I remember with that phrase a sudden ripple of chills washed through my veins. I pulled back from the computer, peering once more toward LA Fresh Poultry and that shitty fiberglass rooster crowning the slaughterhouse rooftop. For a moment, the view felt slightly unreal, and with fresh eyes I wondered how I’d ever washed up here and what I might be stumbling toward.

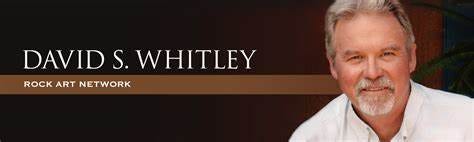

It had been the archaeologist David Whitley who’d first told me about Santa Susana when I met him outside NAWS China Lake in the town of Mojave in July 2014. Months before, in December, David Whitley had delivered a TED Talk about mental illness in ancient people following his ground-breaking research inside France’s Chauvet Cave. I’d worried he might find me mentally unwell if I yacked too much about that rock art coincidence; Whitley had granted it was genuinely “weird” during prior phone conversations. It had been his shamanic rainmaking paper, recall, that paved the way in part for the discovery of that creepy synchronicity that launched my book China Lake. But fortunately, coincidentally, I’d met Ken Caldeira at Stanford only the day before. His assessment that it was all irony slid a sturdy iron lid over that awkward rabbit hole I’d been harboring, which was, after all, exactly what I’d wanted. No more woo-woo.

The was only one dumb ass thing I couldn’t help but blurting out before Dave Whitley.

“Is there anywhere,” I asked him as we wandered the desert lava fields north of the base, “like in Southern California, like around the suburbs somewhere, San Diego maybe, where there’s just like sacred Native American rock art just sitting there?”

While I’d managed to scrap my pathetic suburban memoir, part of me wondered that afternoon if there wasn’t a way to tie things back to my banal San Diego suburban origins, a possible book ending that wasn’t brutally depressing but pointed toward some mystery, some meaning still surviving, a secret lodged in the heart of what I felt to be a hopeless wasteland—my home. I couldn’t help but ask the preeminent authority on California rock art if there were some ancient mystery lurking behind the Westfield Shopping Center where I’d first fingered a girl.

“Is there anywhere,” I went on, “where the art is just sitting there, you know, like basically in plain sight, behind a Starbucks or Regal Cinemas 18 or something?”

I remember Whitley stopped and took off his baseball cap. He dabbed a handkerchief at the sweat falling from a full white head of hair. “Hmm.” Fate seemed to hover in the hot wind that whipped around our shins.

I held my breath. Would I hit on another win?

That was how everything unfolded with that book. I asked a question, a quick random query sprung from some sudden shabby intuition; all the coincidences that kept paving a path toward oblivion throughout the pages of China Lake erupted from the same uncritical impulse. And then the answer would come, either in text or tongue, depending on whether it was the internet or an interviewee.

“That’s a good question,” Whitley said, staring off toward the Sierra.

A dust devil danced below in the dry wash beyond the falls.

But that day it was not to be.

“I don’t think so,” David Whitley said finally.

It was the answer I anticipated. Vindication. All across Southern California, between its millions of miles of road, its 26 million human souls, its 60,000 square miles of real estate running 235 miles from Oprah’s mansion in Montecito south through San Diego to the Tijuana border, there was not a single ancient petroglyph or pictograph of note—no chunk of ancient history or mystery, not a single sacred ceremonial sight, or shamanic pilgrimage point. The thought confirmed my suspicion that the land was cursed. Not only today but yesterday and spanning back across the ages and epochs. Southern California, not just LA, had always been a sterile cultural backwater. “Here, if anywhere else in America,” the Irish poet W.B. Yeats said of Los Angeles in 1925, “I seem to hear the coming footsteps of the muses.” Yes, Mr. Yeats. Did you see the latest Marvel movie? No place on earth ever pumped out such a steady stream of pure amusement. The thought reaffirmed my commitment not to settle in SoCal after I finished China Lake, no matter how Christina begged—and especially not LA.

“Well, actually,” David Whitley said suddenly, replacing his hat. “There is one site.” He gazed off again as if searching for it somewhere beyond the mountains. “It was years ago, back in the mid 90s probably. I’m trying to think where it was exactly.”

Finally, he came up with a place name, one that couldn’t help drain my enthusiasm and cement all skepticism—Los Angeles. But it was weird…

“There was a guard up there who had a Geiger counter. I thought it was some kind of a joke at first. They had armed guards escort us out to the cave. Are you kidding? But then the counter started clicking. It wouldn’t stop clicking.”

And as Whitley went on about an official government cover-up and smuggled plans used to build Chernobyl—words that made me wonder if he wasn’t mentally unwell himself—I mostly forgot about the rock art, especially as it was attached to that putrid place name, Los Angeles, the glitzy television city I’d been bred to believe could never be hiding anything other than its own emptiness. And then, come to find out years later that the site was actually attached to the San Fernando Valley, that notorious municipal appendage, crooked end point of the aqueduct made famous by Polanski’s Chinatown, ground zero of the great art of subdivision, original cradle of that ghastly American dialect, the flapping tongue of our vapid uncultured TV imperialism: Valley Girl…

No, it was impossible. Impossible there was anything important there.

But now as my eyes clicked back from that fiberglass rooster, resuming their research, I felt a small kernel of dread crack in my ribs. It appeared that there really was something there. Something important.

It should not have been there that far south or west but it was—the sole trace of something sacred ever having touched and survived the mocking brilliance of Southern California sky.

“It is likely,” I read with rising pulse, “that the site may have been one of the last, if not the last, important ceremonial site in the general region.”

The phrase “cosmic order” again fired through the cracking flame bucket of my brain, followed by the words rocket and rocchetto—rock art and research. I saw Ken Caldeira swinging round in a swivel chair, calling past the great wide monitor of his latest climate model. “Is there anything more to it than irony!?” No, I told myself. There can’t be. And back in Iowa, behind the Writer’s Workshop, I saw lightning bolts fingering the Hawkeye corn as ravens wandered the empty road, whispering ‘woo, woo’ while the witchy librarian locked the main door. Barred, I sat alone inside a Starbucks waiting for my father to call me back as pale contrails crisscrossed the San Diego sky. All alone, I drove past that green Caltrans sign lying off of CA-395, racing by the murder mines of Red Mountain. And somewhere deep down, at the far edge of the Mojave, I could hear the coming footsteps of the Muse… the mud tiles paving the craters of the Nevada Test Site popping beneath her heels. Click, click went a lone shaman’s quartz hammerstone. Click, click as he pecked out another bighorn on a black slab of desert varnished basalt. “Go deeper,” John D’Agata said. “Go deeper. You’ve only scratched the surface.” And still sitting on the yoga ball, my eyes bored into another blue hyperlink as the bingo numbers blared.

“Seis! Seis! Sies!”

It was almost like I blacked out.

“The coincidence of this prehistoric astronomical site with the location of NASA’s Santa Susana Field Laboratory test areas…

“which helped to develop the earliest manned and unmanned exploration of deep space is notable and should be the subject of both preservation and interpretive efforts.”

“The parallels between the activities of the rocket engineers, the ‘high priests’ of the Cold War and Space Race, and the Chumash Astronomers if not somehow directed by the Land itself, if not actually uncanny, then are at least entirely unprecedented in their co-location.”

“The NASA test stands and the Burro Flats painted shelter comprise the only place on Earth where our modern world heritage in space converges with the prehistoric reach for the sky.”

—Dr. Ed Krupp, archaeoastronomer | Director, Griffith Observatory

It was impossible.

“Both indigenous and modern cultures have occupied the hills… to develop and practice the rituals, ceremonies and technologies that could connect humankind and the heavens.”

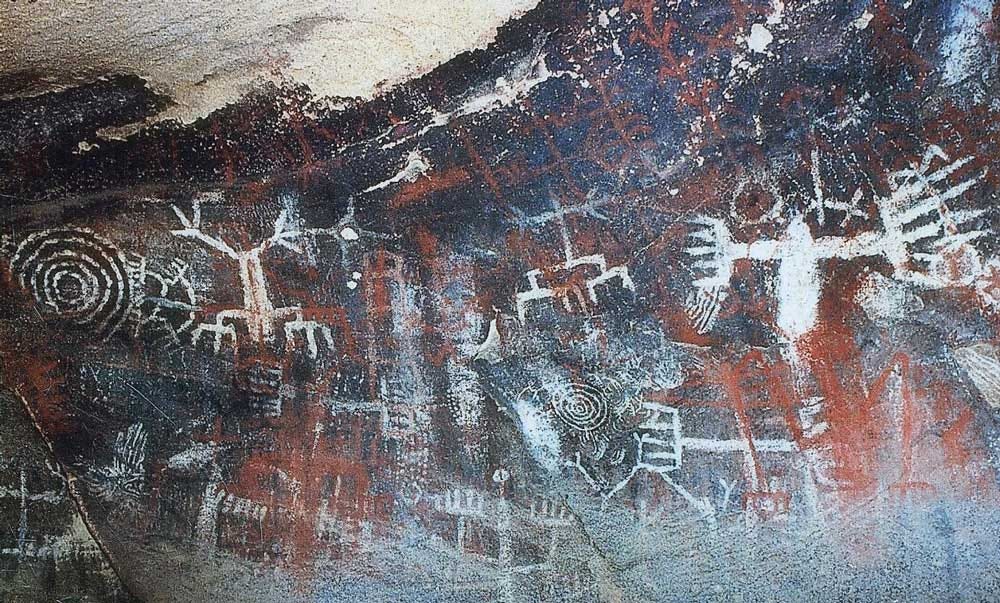

The art was real. And it was painted inside a cave. Dozens of paintings. Paintings a thousand years old and older.

“This is a unique site because it was here that Native Americans looked up at the sky and made cave paintings of the stars. It’s also where we launched rockets into space.”

“Archaeologists who have visited the site have said that it includes some of the most dramatic and best-preserved pictographs known and is among the finest examples of prehistoric pictographic art in North America.”

Paintings inside the cave showed human beings, humanoid figures, ascending toward the heavens. A notch in the mouth of the cave aligned just right to fire them with sunlight during the solstice.

“Nowhere else did two cultures share a space so intensely focused on reaching the heavens…”

It didn’t feel like reading so much as downloading. A sudden blinding injection of information entering my body in one long icy blast. My shivering allotment of brick at the back of Château Westmoreland shot through with the scary cold taste of outer space, iron and meteoric, like a cough drop of lead, and I swallowed carefully as the cold bit down around me.

“The paintings, which record the involvement of the Chumash with the sky, are separated by just a ridge from the stands on which the huge moon-rocket and Space Shuttle engines were test fired.”

Impossible. The cave wasn’t just situated anywhere on Santa Susana’s 2,800 acres. No. The cave was just right there, “on the other side of a ridge from the Apollo test stands…” The cave was only a few hundred feet away, “just a short distance from where, hundreds of years later, humans mastered technologies that defied gravity and allowed them to escape Earth.”

Impossible. This cave, this cavity I’d left unattended at the back of me… It couldn’t be…

The cave was not holding some shitty swastika spraypainted on sandstone by a gothic eighth grader. It did not house the relic of some dismal Disney western aborted in the 1940s. The art wasn’t misidentified by some stoned PhD candidate from nearby CSU Northridge. It wasn’t painted by Charles Manson in the 1960s when the ‘family’ lived in the lower hills at Spahn Ranch fried on LSD. It was not empty. It was not unimportant.

The cave, Burro Flats Cave, at the outskirts of Burro Flats, Portrero de los Burros, was a “place of first-class importance,” a sacred place, Don Juan Menendez, leader of the local Native American community, told anthropologist John P. Harrington in 1917.

It was not nothing. It was the opposite. The true coincidentia oppositorum.

A truly uncanny historical synchronicity. Not nothing but something. A truth shot through with a trace of the numinous. A flicker of terror. Unholy. Sacred. Profane. Totally fucking insane.

It wasn’t possible.

“Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.” —Mark Twain, 1897

And it was just what I had wanted, what I needed, what I kept wishing for the most over those months and years of stagnation and frustration—another coincidence—some kind of crazy collision that might stop me dead in my tracks, deliver the whiff of mystery, the spoor of some uncanny force creeping at the edge of perception—just as I’d encountered at NAWS China Lake. I wanted that frightful, uneasy feeling again that there was something bigger than myself, my cynicism, my education, my sense of right and wrong, the possible and the impossible, moving in upon my existence, looming in from outside, beyond the fence line of the rational mind…

It was the prerequisite for my quest.

No coincidence, no story. Grab it, enjoy it, go… Be brave. Build.

“It’s the only place in the universe,” said Ed Krupp, “that we know of at this moment, where that happened. There could be others. But it happened right here.”

Krupp was right. There could be others, or at least one other. I had made the same mistake myself previously, imagining I had found the only place in the universe where such a coincidence occurred. And now… How was it happening? I hadn’t any business obsessing over any of this horseshit in the first place. I’d just driven past a green Caltrans sign ten times throughout my teens and twenties. I’d remembered the weird name ‘China Lake.’ I never wanted to do research or study rock art. I was some lame navel-gazing kid trying to write creative nonfiction, milking the same sad moments from second grade into mediocre memoir. I exhausted my most cherished and squalid traumas. So on a whim, emboldened by Adderall, I Googled something other than myself one morning. I Googled ‘China Lake’ in April 2013.

And to my utter amazement, after a catastrophic flood and a lot of conspiracy theory and buried history, I’d stumbled upon the impossible…

But it couldn’t happen again. You couldn’t have two cultures and states of art layered one on top of the other, two practices isolated by thousands of years overlapping for generations in a silence as secret and strange as the heavens both sought to ply and propitiate through the technologies of song, art, and trance, engineering, war, and math...

That would be way too uncanny, the heights of weird. Then you’d really have a problem on your hands. Something wayward. Something wrong. Then you’d really have to worry. You’d really have to wonder: What in the fuck was going on? But thankfully, it was impossible.

It was all really quite impossible. It wasn’t happening.

One brush, that was enough.

“Robert Anton Wilson coined the term Chapel Perilous. This is when something happens in your life and it all begins to fit together and make sense, too much sense. Because it’s coming from the exterior and it seems to either mean that you’re losing your mind or you are somehow the central focus of a universal conspiracy that is leading you toward some unimaginable breakthrough… But these are just milestones along the way.

When you finally get to ‘the thing,’ the way you will know that you’ve arrived is that you will be struck dumb with wonder. That you will say, ‘My God, this is impossible. This is inherently impossible. This is what impossible was invented to talk about. This cannot be!’ Then we’re in the ballpark. Then we’re in the presence of the true coincidentia oppositorum.” —Terence Mckenna

And yet, after all that, looking back on that fateful day in March 2017—the release of China Lake only weeks away—what I find perhaps most concerning is that when that coincidence finally came, after a minute of cold shock, I quickly moved on…

As though it meant nothing. As though I knew it were right there all along, a mystery for the taking. One more once in a million chance to annex to my nonfiction launch pad.

I didn’t trouble with the mystery or meaning nor torture myself tallying its miniscule probability. I didn’t waste my time reading up on synchronicity, seriality, panpsychism, quantum physics, or consciousness. I didn’t bother with the muse, daimons, or UFO downloads. I had real work to do. I finally had a book.

And maybe the calm professionalism with which I proceeded to calculate my next move, hurling myself into research, pitching my agent, preparing a book proposal and… proposing to Christina…

Perhaps that’s what determined the disasters that followed: improper paucity of dread.

“Do not call up anything you cannot put down.” —Robert Anton Wilson

Nonfiction books, blogs, and podcasts that have assisted this series so far:

The Flip by

blog by Matt CardinThe Secret Life of Puppets by Victoria Nelson

Sinister Forces by Peter Levenda

The Roots of Coincidence by Arthur Koestler

Also, read this great essay I just found on “Weird Nonfiction” by Clayton Purdon in the Los Angeles Review of Books, September 27, 2024. He nails it.

I’m going to read it all later, just wanted to say I’m honoured to be mentioned and serve as a small source of ontological urging!

Since I’m neither a puffer nor as serious a writer in the same way as yourself, I’m trying to focus on my music more again, let me know if you ever want anything to use in the background of audio versions of your post. Here’s something I recorded the other day:

https://youtu.be/U3pwE28aZ9U

I've stopped "liking" things, especially on here-- too Pavlovian for comfort-- so I want communicate instead how I enjoy your sensibility and appreciate what you seem to be doing with your sentience and how that shows up in your words. Thanks! And thanks for turning me on to The Peregrine. What a sublime document.